Sadler’s Wells, London

October 1, 2025

English National Ballet’s lates R:Evolution programme celebrates four choreographers, each of whom brought innovation to the artform.

Created in 1947, George Balanchine’s Theme and Variations is noted for its meeting of Russian classicism with the speed, precision and attack of America. Although this single movement work was how the ballet was created initially, in 1970, Balanchine returned to Tchaikovsky’s score, choreographing to the rest of it to create Tchaikovsky Suite No.3, which is how New York City Ballet dance it.

The fourth movement, equal in length to the first three movements combined, continues to work superbly on its own, however. The music fits Balanchine’s choreography like a handmade glove. Totally plotless, about the dance and the music and nothing more, it’s quite rightly regarded as one of Balanchine’s best. Danced well, it’s a real showstopper.

The lead roles were taken by guest artists Alice Mariani, principal dancer at La Scala, Milan, and Ricardo Castellanos, principal at Norwegian National Ballet in Oslo. The choreography calls for speed, accuracy and bravura performance. The strikingly fleet of foot Mariani delivered on all counts, showing all the technical brilliance the ballet demands.

Castellanos looked less certain. His footwork was less than neat on occasion with a few steps smudged, a number of landings were heavy, and the final lift was quite a heart in mouth moment as he did well to keep his partner aloft.

The weaving in and out of the corps dancers is as much part of the ballet as the steps for the leading couple. The ensemble supported Mariani and Castellanos very well throughout, although I though the men just edged the women. Things did occasionally look a bit squashed on the Sadler’s Wells stage, though. Perhaps that’s why, overall, it didn’t quite sparkle as it should.

The set is a bit of a disaster. Dark brown flats at the side do not sit comfortably with the plain blue background. And as for the three strips of what look like sad, left-over bits of tinsel hanging from above… Surely they had a chandelier laying around somewhere.

Martha Graham’s Errand into the Maze was created in the same year, in the same city as Balanchine’s masterpiece, but it could come from a totally different world. The most famous, and most commonly danced of her works, it takes inspiration from that classic of Greek mythology, the story of how Theseus entered the labyrinth to slay the Minotaur, navigating his way out with a thread from Ariadne. Graham comes to the story through a female lens, simply calling Ariadne ‘The Woman,’ the Minotaur ‘The Creature of Fear,’ and cutting Theseus entirely. It’s a thrilling, deeply psychological duet when performed well. And it was.

I’m not entirely convinced Graham’s movement vocabulary has quite been captured fully but that’s hardly surprising. It takes a lot more than a couple of weeks of classes. However, as The Woman, Emily Suzuki was wonderfully expressive, jerking and contorting her body as she seeks escape from her maze prison before she eventually overpowered Rentaro Nakaaki’s Creature of Fear into submission. He leaps, while restrained by a staff held at the elbows and back of his neck, not unlike a yoke, were amazing.

William Forsythe’s Herman Schmerman was originally choreographed in 1992 for New York City Ballet, who now only dance its pas de deux. English National Ballet gave us the Quintet, a wonderful section that really allows the dancers to let rip. And isn’t it fabulous when you see they are enjoying themselves as much as those of us watching?

Five dancers dressed in rust-orange in front of a simple Balanchine-like blue backdrop. And like Theme and Variations, Herman Schmerman Quintet is all about the dancing. Whether as individuals, in twos, threes, or all together, Aitor Arrieta, Alice Bellini, Carolyne Galvao, Swanice Luong (who stood out in particular), and Rhys Antoni Yeomans took the breath away, helped along by one of Thom Willem’s less industrial scores.

But the best was still to come. David Dawson is known for choreography that is sleek, extremely physical and emotional. All of that is present in spades in Four Last Songs, made in 2023.

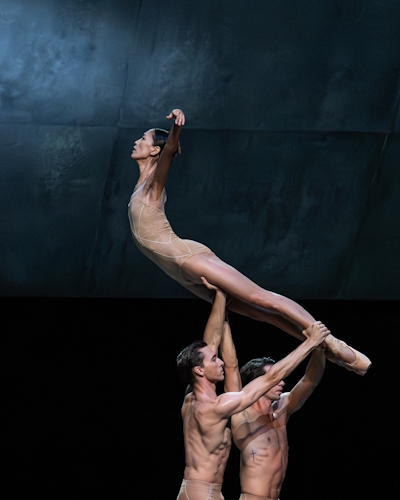

Underneath a concrete slab that could be from a gallery of modernist design, above which is a window onto the sky above, the twelve dancers, the women only in nude-toned leotards, the men only in tights (costumes by Yukimo Takeshima), look like they have stepped out of an old master. As that sky gets increasingly cloudy and dark, the six couples appear like angels, the choreography a perfect match for Richard Strauss’s poignant song cycle that is a farewell to life, so beautifully sung by soprano, Madeleine Pierard. The dancing was certainly divine.

There is much running around, much to and fro, but much soaring too. The number of times the women are carried aloft is staggering. Time and again they look up too, as if eyes are cast towards their heavenly destination. It’s never downcast or gloomy. There’s a sense of not so much an end, as the journey to a new beginning. Poetry in motion, it is utterly, utterly gorgeous.

English National Ballet perform R:Evolution at Sadler’s Wells, London to October 11, 2025.