September 20, 2025

Sadler’s Wells, London

The very first stroke lands in mid-air. Dancers lift their brushes, sketching not only themselves but the edges of the whole world. Lines pull the group together, scatter them, twist them, as if a sketch were constantly shifting in motion.

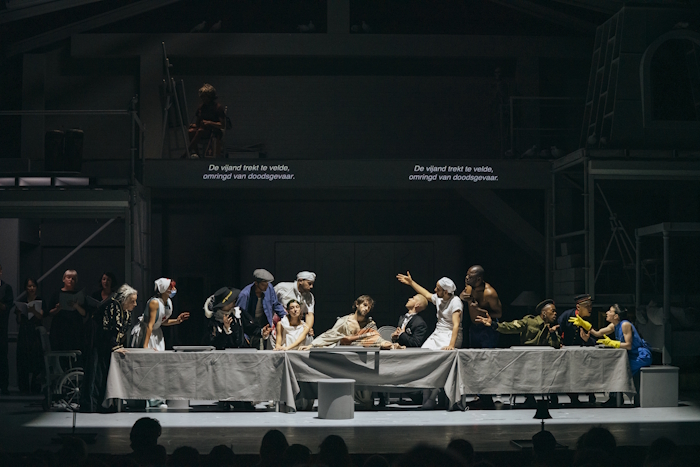

Then she arrives, the female painter. She treats the crowd as her canvas, rearranging bodies into trial sketches. Every so often she stands, studies the shapes they make, and with a flamboyant flick says nothing but a glittering “nope.” Below, dancers strain into position as she keeps redrawing the picture. At last, she lets it be, and the group freezes into a tableau we all know: The Last Supper.

The point here isn’t religion, but order. We watch a familiar image, suddenly realising it’s made of living, breathing bodies. The brush is law, and the crowd is rewritten under its strokes.

in Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui’s Vlaemsch (chez moi)

Photo Filip Van Roe

On our side of the stage, the Sadler’s Wells ‘members’ club’ vibe is thick in the air. People greeting each other, chatting in their own living room. The rules of the theatre are second nature to them. Which throws the title back at us: Chez moi. Whose home is this? Who owns it, and who’s just passing through?

Hans Op de Beeck built the set: a world under a lead-grey filter. White trees, broken columns, oversized books, a skull, “NEVER AGAIN” scrawled on the wall, and a courtroom violence image that could’ve walked straight out of Banksy. Not cosy furniture but a memory warehouse. Grey tones make it all look well-mannered, yet ready to blow. Frames cut through the haze like blades: not just design, but borders. Brushes even sharper: they draw, but they wound. The cleanest sequence of the night was a one-on-one duel, brushes wielded as swords, bodies carving each other in combat before swelling into a group fight, like a dozen sketches scribbled over one another until the lines went bold.

These stage tricks mirror the Picasso exhibition I’d seen at Tate Modern earlier that day. Picasso pulled the human face into planes; Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui pushes geometry back into the body. The red-haired bride bends her spine into saw-teeth, practically a Cubist painting in flesh. In another moment, two dancers sketch lines across a third body, whose limbs are forced to bend and warp with the ‘strokes.’ Three Dancers came instantly to mind. You see it more clearly the longer you watch: Picasso dismembered women on canvas, Cherkaoui dismembers his audience on stage. Different medium, same force.

Off to one side, a giant book, and a skull. Not random props but echoes of Holbein’s The Ambassadors, the famous anamorphic skull stretched across the painting. Holbein filled his canvas with globes, instruments, knowledge, then placed a hidden memento mori at its feet. A reminder: all power, all brilliance, all learning ends in death. Cherkaoui’s book and skull serve the same function. A family archive, yes, but also a warning sign.

Picasso bent women with a brush. Holbein crushed ambassadors with a skull. Cherkaoui piles his house with dancers, books, frames, bones. The house is never steady, never safe. It isn’t a haven. It’s a pressure cooker, stuffed with history, identity, coexistence and its grinding anxieties.

in Vlaemsch (chez moi)

Photo Filip Van Roe

Music is another protagonist. Musical director Floris De Rycker and the early-music ensemble Ratas del Viejo Mundo hold one side of the stage, sending out fifteenth and sixteenth-century polyphony: Machaut, Gombert, Arcadelt. Voices braid like fine wines, layering time on top of time. That ‘utterly peaceful’ music is almost liturgical, while the stage in front of it goes into overdrive. Tsubasa Hori’s soundscapes and percussion crank the tension; breaths snap against drumbeats, only to be soothed by polyphony again. De Rycker himself has talked about Arabic influence on European music, and you hear it slip through the cracks of rhythm and melody. Flemish grey, infused with the world’s counterpoints: Cherkaoui’s DNA made audible.

The cast is like a roaming polyglot choir. Someone chanting, someone declaiming text, someone climbing a broken pillar, someone trapping themselves in a frame. Watching and power keep switching hands. Sometimes the painter has it. Sometimes the group composition itself dictates the body. Sometimes, suddenly, the audience is the one framed. John Berger’s famous line from Ways of Seeing rose up: “Men act, and women appear.” But here it wasn’t just women who were ‘made to appear.’ It was everyone. All were renamed under frames and brushes.

Soetkin Baptist and Darryl E. Woods in Vlaemsch (chez moi)

Photo Filip Van Roe

Vlaemsch (chez moi) is not easy viewing. The simultaneity is brutal: singing on the left, writing on the right, fighting in the middle, subtitles and symbols flying across the back wall. A camera would have picked a focus for you. Live, you have to do the work. I kept drifting off, almost dozing, only to be yanked back by a new image. It was exhausting, but also honest; a stage version of our everyday bombardment. Notifications, feeds, three chats pinging at once. Cherkaoui dumps his brain onstage, and you realise with a jolt that it looks a lot like ours.

A few images are still burned in my mind. The red-haired bride’s spine twisted into jagged lines, but still dancing. The brush duel, clean and sharp, like calligraphy in motion. Frames slipping near and far, trapping, colliding, testing borders. The ‘two painting the third’ scene, a sort of live Three Dancers. Each moment layering over the last, making dance into a painting constantly drawn and erased. And yes, there were stretches that just wore me down: too much data, feelings flattened out. But isn’t that exactly Cherkaoui’s point? His house is crowded, overstuffed, polyglot, polyphonic, poly-everything. Messy to the point of bursting. Which is why it feels so real.

So, here’s my verdict: Cherkaoui’s house is messy, messier than mine. But that’s why I trust him. Because isn’t our reality just as messy? If you want a neat story, Vlaemsch (chez moi) isn’t it. If you want to walk into someone’s mental attic, every drawer flung open, it is.

Credit also to Hans Op de Beeck’s set, which gives the grey its poetry and its menace. Jan-Jan Van Essche’s costumes keep the palette neutral, letting bodies move between frame and brush without distraction. Floris De Rycker and Ratas del Viejo Mundo hold the music’s ground, while Tsubasa Hori twists sound to breaking point. Together, they answer the riddle: Vlaemsch is Flanders, but also the world. Chez moi is my house, but also the theatre seat you’re sitting in.

I can’t possibly write it all down. You’d better go see it yourself. Just remember to pack patience. And maybe bring your own mess to match his.