Linbury Theatre, Royal Ballet & Opera, London

January 29 & 30, 2026

Paul Taylor Dance Company arrived at the Linbury carrying a long American modern-dance lineage. After more than two decades away from the UK, the company returned with two programmes across six works, placing Taylor’s repertoire alongside newer voices that test what his language can still do.

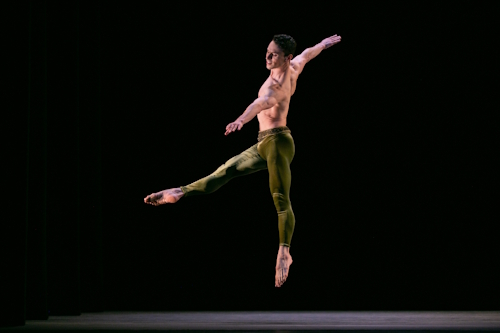

One evening presented Taylor’s Brandenburgs (1988) and Piazzolla Caldera (1997) with the UK premiere of Robert Battle’s Under the Rhythm (2025). The second brought Taylor back in two different registers, late and foundational, with Concertiana (2018) and Esplanade (1975), sandwiching Lauren Lovette’s all-male Echo (2023). Across both evenings, dialects shifted quickly, textures changed sharply, and technique kept surfacing as a through-line. I kept recognising the training logic and grinning like I was eighteen again, back in class, even when I cannot yet pin down what each piece wants beyond its own fluency.

Why the Linbury, why Royal Ballet and Opera now?

The two programmes see the Linbury doing what it does best: making choreography legible at close range. The Royal Ballet & Opera uses the space as a close-viewing platform for dance, bringing modern milestones, new choreographic platforms, and now bringing a two-night ‘snapshot’ of American modern dance into the same frame. The scale matters because the argument lives in detail. From this distance you watch technique becoming theatre in real time: timing, weight shifts, a glance held half a beat longer, musical feeling travelling through faces and shoulders before it reaches the feet.

Taylor’s musical spine

Across both nights, Taylor’s signature stayed unmistakable. He hears music as structure and mood, then builds choreography that lets you watch that hearing take shape. Phrasing, spatial design, even facial energy, track the score’s emotional weather with near-total loyalty. The works rarely settle into a neat ‘aboutness.’ They still offer something concrete. Music becomes visible through bodies.

That logic registers immediately in Brandenburgs. Bach’s brightness meets a classical look, deep green velvet with gold trim, and the movement answers with crisp diagonals, off-centre placement, and fast travelling that stays clean. Pleasure arrives through line and musical clarity. Directional arms keep pointing the space into existence. The body keeps leaving centre, then catching itself, then moving again. Recognition brings a quiet satisfaction. This is movement vocabulary I have lived inside.

Night two confirmed the same instinct in Concertiana. The dancers’ expressions shift with the music’s emotional turns. Diagonals return as choreographic handwriting. Silhouettes cross at the back like edits, cutting through the main action without breaking the flow. Taylor builds a visible structure for the score and asks you to watch the music arrive in flesh.

Then Esplanade opens that method into something public, social, almost celebratory. Fast sections flood into running, jumping, diving, rolling, bodies cutting across the stage as if the music has opened the doors and everyone rushes through. Slow sections soften into extension and breath. Circles keep returning. Canons recur throughout, building a wave-like ensemble texture that stays tightly aligned with the music. In the bright passages it reads like a garden party in motion, social choreography under a classical score. The ending pushes stamina into spectacle, repeated jumps followed by hard drops that look almost reckless. The work also carries physical bluntness: extended floor-work, and a moment where a woman steps on a man’s body, an image that hits with a small jolt inside all that sunshine. I cannot tell you what it ‘means.’ I can tell you it remains enjoyable to watch.

Taylor’s best work survives without a message because form stays alive. Movement keeps generating its own necessity. In weaker moments, the absence of meaning turns into emptiness. Fluency remains. Stakes fail to arrive.

Two nights make the signature unmistakable. Two nights also make the signature loud. Directional arms, constant travelling, cross-stage running and leaping, choreography tracking the score, plus an unusual abundance of smiles. The brightness reads as part of the style. Over two evenings it also starts to feel like a fixed lens.

New voices on a Taylor stage

Robert Battle’s Under the Rhythm entered the first programme with a different accent. The tone leans toward vintage film energy, quick humour, jazz inflections, rhythmic play. Black social-dance textures shift the weight and swing of the room. That shift matters. After Taylor’s upright musical clarity, the centre of gravity changes. Movement starts to sit deeper, to bounce differently, to phrase rhythm through weight.

I enjoy it in the moment. It makes me want to clap along. The dancers look as if they enjoy it too. Then the question follows: what does the work build beyond display, once the collage has shown you everything it can do? The fluency is undeniable. The purpose stays harder to hold.

Desire, display, and the cold patch

The two works that trouble me do it through a related mechanism. They keep presenting ‘heat’ on the surface, but my response stays cool.

In Taylor’s Piazzolla Caldera, tango becomes a banner and the choreography keeps returning to sensual shapes and insinuations. The programme framing promises eroticism. What reaches me feels like tugging, pulling, and the performance of sexiness as repeated gesture. The gestures insist. The temperature stays flat. Borrowing tango’s name, practising the act of pulling, investing in the currency of sexy. I experience the labour of sexiness more than its thrill.

Echo, choreographed by Lauren Lovette, sharpens the same problem. The dancers are beautiful, magnetic, technically strong. The visual benefits are obvious, and I happily applaud the performers. The relational engine never clicks into place. Intimacy reads as distant. Conflict avoids full anger. Play fails to cohere into real togetherness. Sweetness turns sour too quickly, and the shifts feel unearned. The choreography changes states; consequence rarely shows up. Without consequence, the relationships stay thin, and the piece starts asking the audience to supply an emotional logic it has not built. I grow impatient. I catch myself wanting it to end. At that point the dance risks collapsing into its surface offer: bodies, ability, display. The visual perks are generous. Even that cannot hold me. The work keeps asking for attention it has not earned.

Taken together, the six works show a repertoire with a strong musical spine and a highly recognisable choreographic voice. Taylor’s craft keeps making the score visible. Two nights also reveal the cost of a clear signature when you see it repeatedly. My own thread stays simple, and very me. I smile when I recognise the vocabulary of training. That smile carries nostalgia and pleasure. It also becomes a test. Fluency can dazzle. Fluency still needs a reason to exist in front of us.