(LA)HORDE and Rambert, Southbank Centre, London

September 3, 2025

Presented by (LA)HORDE with Ballet national de Marseille and Rambert at the Southbank Centre, We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon is a collaborative exploration of fragmented narratives and contemporary desires. Featuring choreographies by (LA)HORDE, Benoit Swan Pouffer, Cécilia Bengolea and François Chaignaud, Lucinda Childs, and Oona Doherty, the programme unfolded as a deliberately fractured whole across multiple spaces, from stage to foyer to rooftop.

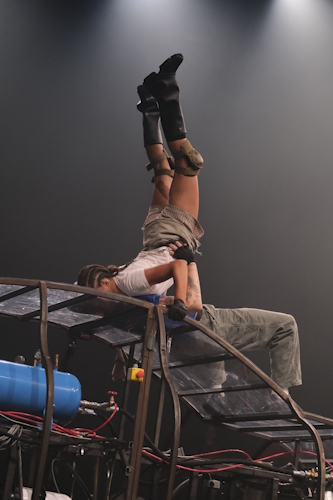

We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon resists coherence, mirroring the fractured pulse of our time. What it offers is not a story but a cascade of fragments: moments of absurdity, flashes of beauty, sudden surges of energy. In ‘Weather is Sweet,’ choreographed by (LA)HORDE, six dancers writhe insect-like, straining for eroticism but tipping into absurdity. It’s so overwrought it becomes almost comic. In ‘Low Rider,’ also from (LA)HORDE, a car bounces furiously, performers on its roof enacting a pantomime of intimacy so exaggerated it verges on the farcical. Elsewhere, a stage transforms into a nightclub, while in the foyer, the DJ seemed more alive than the dancers he accompanied.

The audience, too, becomes part of the performance. On the rooftop, during an undressing sequence, soft chuckles accompany the men removing their clothes, perhaps laughter born of embarrassment, their bodies exposed under glass. When a woman undresses, the room grows fuller, quieter. Watching the watchers feels as integral as the action itself.

Film and video serve as playful counterpoints. ‘Ghosts,’ a short film by (LA)HORDE with a script by Spike Jonze, evokes Night at the Museum, with spirits wreaking havoc in a gallery until a security guard, smiling, danced his way out in a surprisingly satisfying ending. By contrast, ‘Culted/Baptemes’ crafts a transcendent image: the organ’s sudden blast, baptismal gestures, and a final immersion into water.

Between these sharper images are passages of atmosphere: dancers hurling their bodies across the stage, limbs slicing through the air like interrupted conversations, or moving as if caught in a party’s pulse. They don’t always linger in memory, yet they reinforce We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon as an experience of collisions and moods that dissolve as quickly as they appear.

Amid the noise, moments of intensity emerge. In ‘Grime Ballet’ by Bengolea and Chaignaud, four men on pointe offer a comic yet arresting vocabulary, perhaps a sly nod to ballet’s gender conventions.

In ‘Concerto,’ Lucinda Childs’ minimalist clarity flickers through the chaos, her geometric patterns tracing precise lines across the stage, a fleeting order amid relentless fragmentation.

In ‘Lazarus,’ Oona Doherty’s voice comes through most clearly: a female dancer’s natural, relaxed body channelled anger, confusion, and a devastating smile-into-tears, giving the chaos its most unforgettable focus. Doherty’s choreography demanded vulnerability in its sudden collapses, shouts, and gestures torn from everyday survival. Against Childs’ geometry, her visceral realism underscored the deliberate clash of vocabularies that defined the evening.

What holds these disparate episodes together is (LA)HORDE’s orchestration of space. Moving audiences between the Queen Elizabeth Hall, the foyer, and the rooftop is not merely logistical but thematic: fragmentation becomes spatial. On the rooftop, the glass ceiling intensified the intimacy of the undressing sequence, turning spectators into voyeurs within a confined, almost cinematic frame. Each shift unsettled perspective, making viewers conscious of their own movement as part of the choreography. The work’s fractured structure risked disorientation, but it mirrored the experience of living in a world overwhelmed by fleeting images and shifting platforms.

Beneath the absurdity, We Should Have Never Walked On The Moon mirrors our moment: the glow of phones, the pulse of club beats, sex drained of intimacy and recycled as spectacle. Technology may have carried us to the moon, but on the ground, it leaves us fragmented, estranged. The evening’s images embodied both achievement and collapse; the exhilaration of bodies amplified by machines, the loneliness of desire consumed as distraction.

The finale left dancers and audience visibly delighted, yet its essence remained elusive. Still, its chaotic vitality captured a generation adrift in spectacle and sensation, provoked and unsettled, if only fleetingly coherent. In its refusal to cohere, the evening challenged contemporary dance to embrace chaos as a mirror of our fractured world, leaving an indelible, if disorienting, mark.