Linbury Theatre, Royal Ballet & Opera, London

November 10, 2025

She is undoubtedly a star of the present generation of ballet dancers and, like so many, she’s interested in exploring dance beyond the classical form. This impressive in every way, self-curated programme, certainly does that.

Without doubt, the highlight is the return of The Exhibition, Norwegian choreographer Jo Strømgren tale of the accidental meeting of two people in a gallery. Two people who have absolutely nothing in common, but whose coming together reveals much about its two protaganists: who they really are, their vulnerabilities and emotions. And with plenty of humour along the way.

They are an odd couple. The well-turned-out Osipova (heels, smart raincoat, fashionable trousers) and the scruffy Christopher Akrill (khaki parka, jeans, woolly hat, old trainers) collide in front of a painting. There’s frustration, some prejudice that might make you squirm, and then much mischief as a relationship develops, the fun helped enormously by her speaking Russian, him English, and neither, apparently, having much clue about what the other is saying, other what they get from tone and body language.

But, bit by bit, they work out a way of understanding each other; to the point where we hear about her abused childhood, told as she sits sculpture-like on a pedestal, and his cruelty to a cat. Suddenly, her confidence and audacity in particualr seems a million miles away.

The choreography is not particularly complex or demanding but it is a super piece of theatre in which both Osipova and Akrill make you identify with them and the work’s deeper messages. Not being able to understand her just makes it even more fun.

Best of all is the ease with which Osipova plays her part. Her facial expressions, seen clearly in the intimate Linbury Theatre, are a delight. Not far in, you start to see the cheekiness and a lovely glint in her eye that tells you she’s actually playing him along. And she does drop into English later on.

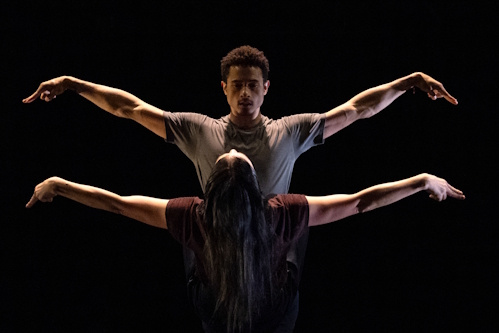

Opening the programme was a revised version of Alexei Ratmansky’s 1998 ten-minute work, Middle Duet, originally set to Yuri Khanin’s Middle Symphony. Called Middle Duet II, it is performed to a new score by Philip Feeney, and danced by Osipova and Patricio Revé.

The couple dance a spiky duet under the watching gaze of a Black Angel and a White Angel. It is classical yet with a decided contemporary edge. There’s lot of turn in and out. Osipova’s legs in particular sliced through the air like the sharpest of knives. Whether we’re watching a love affair, or just life is unclear, but when the collapse to the floor, the angels make their move, raising the couple before Katie Robertson and Blake Smith appear as younger-looking versions of the original pair. It’s a fascinating piece that shows just what a talent Ratmansky was, even then.

Next up, Grigory Dobrygin’s film of Osipova dancing Frederick Ashton’s Five Brahms Waltzes in the Manner of Isadora Duncan is surprisingly powerful. As a work, it’s never been a personal favourite, but the empty warehouse-like space at Alexandra Palace, all dusty shadows and bare floorboards suits it perfectly. Somehow, the space seems to allow the choreography to breathe to its fullest, allowing its childlike qualities to burst forth. At times, you wonder how cinematographer Mikhail Krichman kept up with her. More natural than any rendition I’ve ever seen on a live stage, it is a real gem.

Mud of Sorrow is a duet from Akram Khan’s acclaimed collaboration with Sylvie Guillem, Sacred Monsters, which rather scarily was eighteen years ago. Time flies. Set to the Corsican folk song, U lamentu di ghjesù (The Lament of Jesus), it appears very much to be a dance of a close relationship that was, and for reasons unexplained, is no more. Osipova spends much time clinging to Revé with her legs, leaning forwards and back, their two bodies forever entwined, memories that can never be forgotten.